Kant was a truly great philosopher. He didn’t just fill gaps or take ideas to their logical conclusion; he genuinely advanced the field. Or at least he would have if half the field wasn’t too busy worshiping him and the other half ignoring him. Poor Kant. Too popular and too vilified to be taken seriously. But take him seriously we must, for Kant’s was a profound insight that sowed the seeds of a bitter schism – one that, even in this age of inclusion, remains ruthlessly enforced – and gave philosophy a mighty sword with which to retake the academic throne – if it could only see itself as worthy.

Kant’s genius lay in a strategy for defeating the mighty scourge of antinomy: the dreaded pull of opposition that pervades all human knowledge and endeavor. Imagine a wishbone being pulled apart but where reason is the only thing breakable. You have antinomy when reason demands that something both must, and can’t, be true. There must have been a first cause (because everything has to come from something), there can’t have been a first cause (because then something would have had to come from nothing). Human action must be free (since we are morally responsible), human action can’t be free (since every act is predetermined). Those are Kant’s examples. He gave two others.

The most important thing to understand about antinomies is that there aren’t just four of them. There are frighteningly many: perhaps as many as there are disagreements. Delve into any philosophical dispute and you’ll find them just below the surface, scurrying around like sand crabs, quietly directing traffic. Fall down a philosophical rabbit hole – any philosophical rabbit hole – and you’ll crack your skull on one antinomy after another: realism or anti-realism, naturalism or non-naturalism, internalism or externalism, objectivism or subjectivism, or whatever the bifurcation du jour. There’s no official registry of the era’s most eligible antinomies but a popular survey of philosophers’ beliefs comes close: “A priori knowledge: no or yes?” “Abstract objects: platonism or nominalism?” “Aesthetic value: objective or subjective?” Which side are you on, boys? Which side are you on?

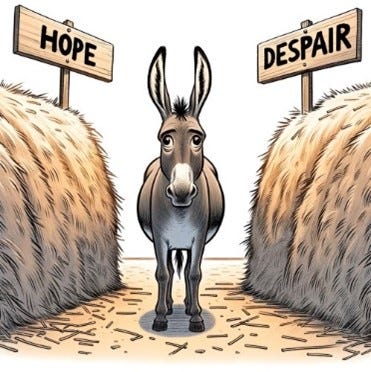

Like Buridan’s fabled ass, reason often finds itself equidistant between two equally luscious bales of hay, having reason to prefer each bale but no reason to prefer the one to the other.

You might brush all this off as just so much academic tail-chasing. But antinomies can bite you in the tail quite literally. Ever get stuck in a mind loop, oscillating between opposites, no exit ramp in sight? You must tell someone off, you can’t tell them off; you must confess your love, you can’t confess your love; you have to tell your spouse, you can’t tell your spouse; you must go home, you can’t go home; you have to leave, you can’t leave. Like Buridan’s fabled ass, reason often finds itself equidistant between two equally luscious bales of hay, having reason to prefer each bale but no reason to prefer the one to the other. Our feelings can be just as powerful and just as fickle, capable of equal parts love and resentment, admiration and hate, fear and awe. Antinomies, alas, don’t just live in ivory towers. They spare neither thoughts nor feelings. They can delight us with their riddles. They can devour us from within.

From whence these curious creatures? Who spawned these bifurcated imps? Medieval antinomies took aim mainly at God, whose perfection and contradiction were such that none greater could be conceived. God must be all-powerful, God can’t be all-powerful; God must be part of the universe, God can’t be part of the universe; God must be able to intend evil, God can’t intend evil; God must exist, God can’t exist. And on it went. A more reliable test of faith can scarcely be imagined. Or would it be the least reliable, since who but the truly divine could be so thoroughly and enigmatically conflicted? No, it must be the most reliable. No, it can’t be the most reliable. Help me Immanuel Kant; you’re my only hope.

The contents of Pandora’s box, like the contents of Al Capone’s vault, are a mystery (just ask Geraldo Rivera). And if this essay were an episode of Ancient Aliens I just might cue the music, crank up the earnestness, stare into the camera and ask: “Could it have contained ANTINOMIES?” It’s possible. But what’s not possible is to read Greek mythology without tripping over one antinomy after another. Apollo is the god of light and healing but also of destruction and plague. Dionysus is the god of ecstasy and madness, bringer of sorrow and joy. Mortals and gods alike are free although their fates have already been written. The Greeks were obsessed with antinomies. It’s why their stories fascinate us still.

And no Greek was more obsessed than Socrates, whose preferred method of argument was to show that his opponent’s view entailed a contradiction and thus couldn’t be redeemed. And he was good, adeptly driving them to contradiction no matter which view or side they took. Indeed, he possessed the peculiar skill of being able to defeat both sides of an argument: to show that both P and not-P entailed contradictions. Talk about impiety and corrupting the youth! But it was Kant who grasped that to defeat both sides was not to defeat the antinomy itself because its two sides cannot be simultaneously defeated. They’re in direct and symbiotic opposition; deflate the one and you inflate the other. Besides, there’s no victory in hitting a fork in the road and proving both paths untenable. And Kant was playing to win.

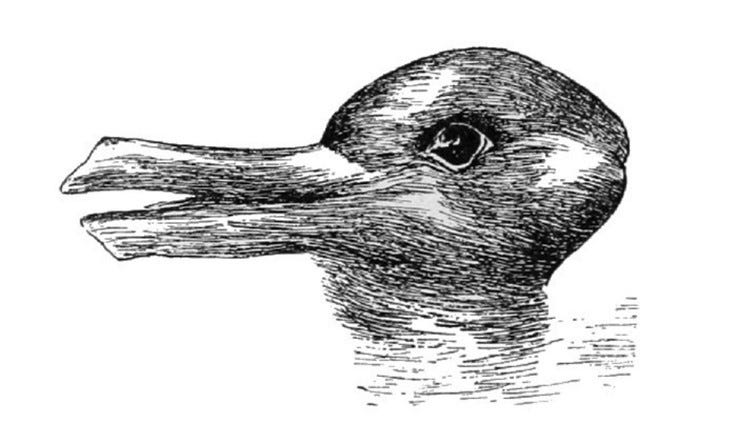

Kant’s idea was that, when you come upon an antinomy, don’t panic, scream, or play dead. Stand your ground. Treat it like the duckrabbit illusion. Try to see it from one side and then the other. P must be Q. P can’t be Q. P must be Q. P can’t be Q. Get in that headspace. Now, as you vacillate, you might find yourself leaning. “I swear it’s more duck than rabbit,” you might say. But that’s just your Stockholm Syndrome talking. Remember: the antinomy wants you to take sides. It needs you to take sides. And make no mistake: you will be tempted. But you will resist. For you, good citizen, are a Kantian. And your moment of glory awaits, if not in this life then surely in the next.

Perceptual inconsistencies reveal something about how vision works: how the mind constructs perceptual reality. Mental inconsistencies – antinomies – reveal something about how thinking works: how the mind constructs conceptual reality.

What Kant does next is the equivalent of David Copperfield making the Statue of Liberty disappear, because it’s all misdirection. The trick is to distract the antinomy long enough to disarm it by refusing to play its game. Instead of taking sides – marching under “duck” or “rabbit” – you ask: what is the antinomy’s source? Why do we find both sides compelling? What does it say about the mind that, here, of all places, we’re being asked to choose? Remember the dress that broke the internet? Is it blue or black or white or gold? Resist the urge to take sides! There is a deeper insight to be had. Perceptual inconsistencies reveal something about how vision works: how the mind constructs perceptual reality. Mental inconsistencies – antinomies – reveal something about how thinking works: how the mind constructs conceptual reality.

Like Dr. Frankenstein, Kant made the classic error of not fully grasping the profundity of his own creation. For Kant, the antinomies were limits on reason’s scope: signs that it has ventured beyond its purview into realms indecipherable and unknown and about which talk is cheap. The antinomies were guardrails and Kant a crabby crossing guard telling reason to stay in its lane. But that is a command that reason can neither heed nor fathom. Like a 1980s teenager its self-conception is that it’s all-powerful. No one puts reason in the corner – not even reason herself! Besides, how feeble could reason be if Kant had just used it to demonstrate its own limitations? But it was probably the sting of insult – Kant telling reason, and thus philosophers, that they were out of their depth – that best explains why half the field decided to defect.

But, by his own lights, Kant was wrong to put reason in a corner. His project was to understand the mind and how it organizes sense experience to produce what we take to be reality. Organization requires distinction which requires bifurcation. To organize a closet you distinguish shirts from pants and ties from socks. But first you must bifurcate: clothes and not-clothes, shirts and not-shirts, socks and not-socks. Antinomies are bifurcations in thought. They’re the grooves in which thoughts travel – the principles of mental organization themselves. How your closet looks depends on how you bifurcate clothes; how you think depends on how you bifurcate ideas.

And so Kant didn’t confine reason; he liberated it from the yoke of antinomy. Before Kant, reason would probe, hit an antinomy, and get stuck, like a wagon wheel in mud. The best reasoners were those who could drag you into mud the fastest and who, when on the receiving end of such treatment, could hold out the longest. But they couldn’t outrun the mud either. Eventually they’d hit a fork – an impasse between opposing views, both of which could be defended, neither of which could defeat the other – and they’d have no choice but to withdraw or take sides. And so they mostly took sides. And then they took sides of sides. And on it went. The more they reasoned, the more antinomies they discovered, the more sectarian they became.

How your closet looks depends on how you bifurcate clothes; how you think depends on how you bifurcate ideas.

After Kant, reason had a way to outrun the mud. Reason, Kant reasoned, shouldn’t fear antinomy; it should use it, ruthlessly, remorselessly, merely as a means. Antinomies are not the end of inquiry but only the beginning. Find one in therapy – I can’t confront my mother, I must confront my mother – and you’ve made progress. Find one in testimony – I couldn’t have left my house, I must have left my house – and you have the makings of a case. Find one in philosophy and you’ve given reason a way to grasp its own operations: to understand thought itself. But first you must refuse to choose.

Such thoughts of thought itself revealed must have permeated the late 18th century air. Imagine, the enlightenment turning inwards, trying to understand its own appearances, becoming self-aware. And scholars, ironically, would be pressed to take sides. For in liberating reason Kant had conjured an antinomy of his own. It was the antinomy of antinomies – one to rule them all and in the light divide them – and, like a good deontologist, Kant had tossed it into the bubbling ferment without a qualm as to the consequences. And there it sat, then stirred, then percolated, until the ground above began to split, barely perceptibly, inch by inch. Until one day scholars looked up from their podiums and found their erstwhile colleagues unrecognizable.

There’s no particular time at which the great decoupling began or when it was completed but there is no doubt that Kant had sowed the seeds. Having forged Excalibur, he had cursed philosophers with the burden of having to decide whether to use it. It was a choice between conservatism and progressivism, stasis and change, old and new. Two thousand years of trying to connect the dots had produced an output both remarkable and underwhelming. Do you pull back or double down? Change paths or stay the course? Failure, they say, is an orphan. But its explanations always come in pairs: we did too much, we didn’t do enough. Which side are you on, boys? Which side are you on?

The Analytics put their faith in dissection. If only those bifurcated imps (the antinomies and not the philosophers!) could be captured, isolated, and disassembled – if they could be stated with maximal clarity, without ambiguity or equivocation, reduced to their most fundamental elements – then and only then would one side wither, the other shine, and all such impishness be banished. These brave warriors were prepared to go the distance. Logic would be their scalpel and clarity their cause. Reason – divorced from religion and sentiment – would outwit contradiction. You have to admire their pluck.

The Continentals befriended contradiction or at least tried to woo it. None flattered it more shamelessly than Hegel, for whom it became the engine of change, the essence of thought, mover of history’s great wheel. Darwin is credited with the theory of evolution but it was Hegel who first presented that theory in its most general form – not of biological life in particular but of change in general – governed by a kind of natural selection. Only for Hegel the selector wasn’t scarcity, predation, or variation but a dialectical process – a mosh pit wherein opposing ideas clash, unite, and are transformed – all powered by contradiction and the need to resolve it. Philosophy’s greatest bogeyman had become its greatest asset; what was once to be avoided was suddenly the key to unraveling it all.

The Analytics, meanwhile, took advantage of lax ethics rules to subject antinomies to ever greater cruelties and humiliations. Theirs was to strip philosophy of any possible unclarity. And so they set about studying (and often advancing) mathematics, from which they hoped to learn a language so precise that no antinomy could ever feel safe. Aristotle’s logic, having stood for two millennia, buckled under the weight of the new demand for clarity. New logical functions were invented. Propositions – units of thought – were shown to have deeper structure that could be penetrated by analytic techniques. The race for glory – which side would be the first to slay the mighty scourge – was on.

Who but a poet could explain how a jigsaw puzzle could consist of only two pieces that don’t quite fit together? And who but a mathematician could demonstrate beyond all doubt that the two pieces won’t fit together no matter how they’re arranged?

But in the end both sides chose poorly. Because the first rule of antinomy club is that you can’t choose your way out of an antinomy, even if it takes its own form as its subject. Defeating antinomies requires true enlightenment: seeing how both sides are right. As they were. The Analytics were right to ignore Kantian exuberance. There were many antinomies still to be discovered and many more to be dissolved. “Is it actually an antinomy or does it just seem like one?” remained a vital question. The world, you could say, needed analytic philosophers to find the true contradictions. And the Continentals were right to behold Excalibur. The old ways foretold of sectarianism and mudslides. Philosophy needed contradictions to illuminate the mind and not just to map conceptual space or to eliminate options. For two millennia philosophers had wandered the desert wrestling with the same questions that had bedeviled their founder. At last they sensed that they could turn what had bedeviled him into a theory of everything. What choice did they have?

The Continentals accuse the Analytics of wishing they were mathematicians. The Analytics accuse the Continentals of wishing they were poets. Each side accuses the other of pretending to be something that they aren’t. But the truth is weirder still: they’re each pretending to be something that they are. For what is poetry but a stab at unifying disparities and embracing contradictions: at letting P and not-P coexist? Who but a poet could explain how a jigsaw puzzle could consist of only two pieces that don’t quite fit together? And who but a mathematician could demonstrate beyond all doubt that the two pieces won’t fit together no matter how they’re arranged?

In the fifth season of BoJack Horseman, a character must mediate a dispute between two comedy writers who practice an odd division of labor: one writes just the set-ups and the other just the punchlines. Their dispute is over whose job is harder: a fascinating question that the show, alas, doesn’t bother to resolve. Whatever the answer, each writer would probably benefit from having time apart; freed from having to please the other there’s no telling how their creativity might flourish. One might find a way to write set-ups so pungent as to make punchlines practically redundant; the other to write punchlines so elastic as to make set-ups outworn. But in the end their creativity would betray them because they are symbiotic. There is no joke without them both.

A house divided cannot stand. A house divided must stand. For every house is divided. Structure is just parts in opposition. And parts in opposition are the real hopeless romantics because they truly need each other. And what is philosophy but a refuge for hopeless romantics? And what is more satisfying than when two hopeless romantics realize that it’s the other that they need? Neither can defeat the mighty scourge alone. Philosophy requires a set-up and a punchline. Poetry without math is empty; math without poetry is blind.

Very nice Kant-antinomy piece. Some people actually read Kant only for the ethics.

Hard to imagine.

Inspired by your paper, I boldly advocate accepting that we live in an antinomic universe. Antinomies are everywhere and increasing rapidly --- sort like tribbles . . . if tribbles had fangs . . . and an injectable neurotoxin.

Two quick cases.

(1) The Quantum Physics notion of superposition. A particle may have, say, spin up and spin down. This is NOT a contradiction, say the physicists, since the two spins are in superposition, they are not occurring at the same time and place. But this is just Quantum physicist trepidation: A single particle can have 2 opposing spins at the same time and place. How? Shrug: The spins are antinomies — contradictory. This happens throughout physics.

(2) Consider the set of even numbers (E). It has the same cardinality as the set of natural numbers (N), aleph-null. Proof: E can be put into one-to-one correspondence with N. So, E and N are the same “size.” But clearly E is “smaller” than N: E lacks all the odd numbers but the odds are completely in attendance in N, along with everything else. So E is both smaller than and the same size as N. Mathematicians hate this, by and large. But some embrace it. And of course, math is crawling with antinomies.

We philosophers should embrace that we live in an Antinomic Universe. Contradiction is that rough beast, it’s hour come round at last . . . after logical empiricism and all similar big-tent philosophies since Parmenides have failed . . . slouching towards Athens to be born.

Or, to end on a more upbeat note: There is grandeur in this view of our universe with its contradictory powers breathed into all. And whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the more-or-less fixed law of gravity, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been and still are being . . . contradictory.

such great writing! lax ethics rules and safe spaces for antinomies. a wishbone breaking at reason. a house divided must stand. and i especially appreciated the "erstwhile".