One of the first philosophy classes I ever took was an early modern survey course on Descartes, Hume, and Kant. We began with Descartes’ Meditations. And though it was occasionally dense and difficult, by the end I felt I got the gist of it. Hume’s Enquiry came next. It too was dense and difficult. But, by the end, and with some re-reading, I felt I got the gist of it as well.

Hume had left us – or at least the five of us paying close attention – dumbstruck. He had seemingly outwitted reason, chopped its legs off, buried it under the weight of its own demands. How, we wondered, was Kant going to revive it? How would he save philosophy from the hole that Hume had dug for it? How would he convince us that we wouldn’t be groping in the dark forever?

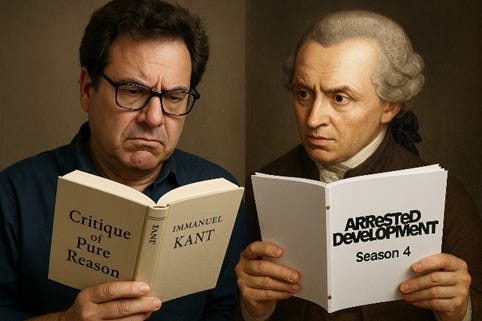

Giddy with anticipation, we turned to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. And, within hours, I was groping in the dark. The Critique was impenetrable. It may as well have been written in Sanskrit. I mostly understood the words (though Kant introduces many new ones), less so the sentences, and less so the paragraphs. The chapters were a blur. Re-reading was no help. I did what I could to keep up, but it was soon clear that I hadn’t actually fallen behind because everyone, including the instructor, was mystified. Beyond the basics, none of us had any idea what Kant was saying. We all felt bewildered, unmoored, and betrayed: just how fans of Arrested Development felt when they first watched the fourth season.

Anticipation

2011 was a banner year. Obama was still cool. Jon Stewart was still funny. Game of Thrones premiered on HBO. The kids were really into planking—not a sexual position but just as dorky as it sounds. And Arrested Development – a show headed for comedy’s pantheon before its development was abruptly arrested, in 2006, midway through its third season – officially announced that it was bringing the Bluths back for another go. Only, we’d have to wait until 2013.

But holy shit were we excited. For those too young or too unscarred by fucked up childhoods to appreciate it, Arrested Development wasn’t just another sitcom. It was an epiphany and a culmination: the final gasp and purest distillation of recursive, self-referential Gen X humor. The great sitcoms that followed, like The Office (2005-2013) and 30 Rock (2006-2013), were already dripping in millennial earnestness. Arrested Development stood alone as the high-water mark of Gen X absurdity, insouciance, and amorality: every action had consequences and nothing mattered.

A Closed System

But what was Arrested Development really about?

If Cheers was about friendship and Seinfeld was about nothing, then Arrested Development was about incest. The show was structurally incestuous – a hall of mirrors – a closed system kept afloat through recombination, self-reference, and internal churn. Its outputs were its inputs; its punchlines were its set-ups; its best jokes were about its own jokes. Even the names were recycled (“Gob” stands for “George Oscar Bluth”). The show told the story of a family turned inward, mutually co-dependent, unable to form relationships with anyone but themselves. Every character made sense within the family but not outside it. Without his family to save, Michael is lost and aimless. Without Michael to compete against, Gob is just sad. Without her family to defy, Lindsay has no identity at all.

Just about every character, moreover, was implicated in some incestuous entanglement. Fans will remember George Michael’s love for his cousin Maeby and Buster’s for his mother Lucille. But Lucille also had a not-so-subtle thing for her son Michael, as did his brother Gob, sister Lindsay and her husband Tobias. Quite literally, “Family Love Michael.”

Lucille – the matriarch – slept as much with her husband George as with his twin brother Oscar. Lucille II (Liza Minnelli) – a mother/matriarch substitute – is the family’s Oedipal swiss army knife, bedding George, Oscar, Buster, Job, and, almost, Michael, whom she rejects on principle (but not the principle that she’s already bedded half his family).

And that’s just the tip of the incestuous iceberg. Gob dates George Michael’s girlfriend (Ann); Michael dates Gob’s girlfriend (Marta); Lindsay tries to date her daughter Maeby’s boyfriend (Steve Holt!), who happens to be Gob’s son and thus Maeby’s cousin (though maybe not her “real cousin”). At the end of the third season, Lindsay discovers that she might not be a Bluth (and thus not Michael’s “real sister”) and so she throws herself at Michael. Gob sees Michael reject Lindsay and throws himself at her.

In one episode, Jason Bateman’s (Michael’s) real life sister – Justine Bateman – plays a prostitute who flirts with Michael while being pimped out by his brother. Even the casting was incestuous.

And it was all hysterically funny.

The Fourth Season

It’s hard to recall just how I felt back in 2013 watching the fourth season’s first episode – the one about Michael – but my face, I’m sure, resembled a party balloon deflating. Picture a campaign worker on election night as it slowly dawns on her that her candidate is going to lose.

The characters seemed cartoonish, the plot tedious, the jokes contrived. Michael spends half the episode reconstructing every permutation of a voting scheme that he concocts to get rid of George Michael’s roommate P-Hound, who, he tells George Michael, is “yanking our chain again.” Largely gone were the cuts to other characters and their intersecting lives. Gone was the crackling energy. Gone was the joy. A show that had thrived because, as Lucille had put it, it “didn’t seem desperate” – suddenly seemed very desperate.

But I stuck it out and watched all fifteen episodes. And then, about a year later, I re-watched them. And the scales fell from my eyes. Because the fourth season is not just Arrested Development’s best season but a work of profound, intricate genius, much like Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.

The Banality of Genius

I doubt that Mitchell Hurwitz – the creator of Arrested Development – set out to make a season that, upon first viewing, would be unwatchable. I also doubt that Immanuel Kant – the creator of transcendental idealism – set out to write a book that, upon first reading, would be unreadable. But that’s just what they did. And thank God they had.

The thing about the fourth season – why it’s so dull upon first viewing – is that you have no grasp of the whole story and thus no sense of how the parts fit together. It’s like seeing a tapestry one square at a time and in no particular order. But, as more squares are revealed, the tapestry takes shape, and each prior reveal retroactively acquires new meaning.

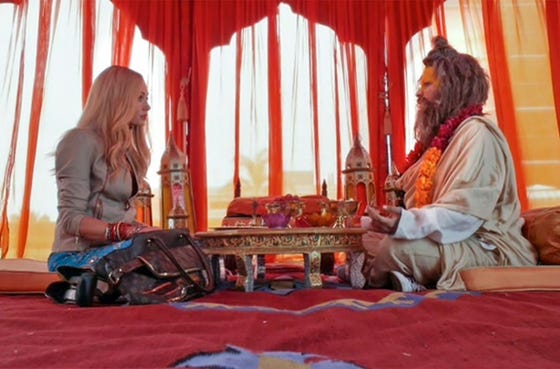

I re-watched the first episode and found it weirdly enjoyable. Knowing the whole story, the opening dialogue between Michael and Gob – culminating in an oddly smooth pair of legs appearing on the stairs and Gob force-feeding Michael a “forget-me-now” – no longer seemed stilted. The third episode – in which Lindsay travels to India – is tedious upon first watching but brilliant after you’ve seen the fifth, where it’s revealed that Tobias had come along unwittingly. But the real payoff is in the twelfth, where we learn the identity of the shaman that Lindsay had visited and whose advice she’d taken to heart.

Excavation

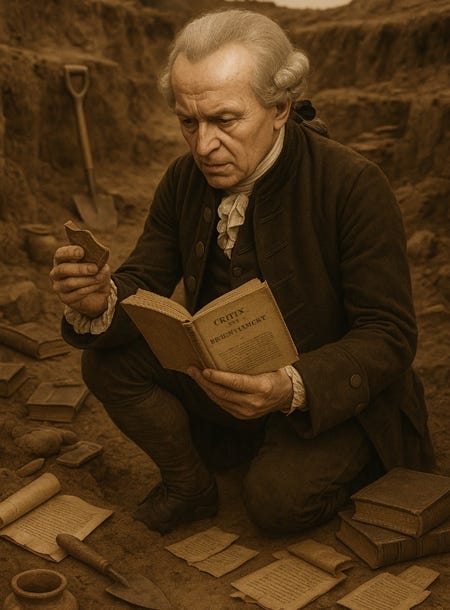

Descartes, Hume, and Kant were all systematic thinkers. But whereas Descartes and Hume assembled their systems step by step, from mutually independent parts, Kant’s approach, like Hurwitz’s, was architectonic: a unified whole in which every part derives its meaning from its place within the system.

With Descartes and Hume, you can follow the assembly step by step. You can take their systems apart, add or remove elements, and put them back together. That’s why, when you come upon obscure sections, you can just re-read them. With Kant, however, re-reading sections isn’t much help. You can’t understand sections in isolation; to grasp the parts you have to grasp the whole. In a sense, you have to already understand him in order to begin to understand him.

Kant, like Hurwitz, is more excavator than builder. The structure is there but buried. To see it, you have to remove everything that obscures it. At first, the uncovered fragments seem disconnected and random. But, once enough dirt has been cleared, the whole comes into view, and the uncovered fragments retroactively acquire new meaning.

The Categorical Imperative

If you want to follow up on Lindsay, you can’t just watch the “Lindsay” episode. And if you want to understand Kant’s ethics, you can’t just watch the “ethics” episode. You have to go back to the beginning – to the first episode – to Kant’s theory of mind. So let’s (very briefly!) excavate Kant’s ethics, beginning with his radical inversion of what was then the dominant mental model.

Look around you. How many objects do you see? The answer is that it depends on how your mind draws boundaries – how it carves and slices – how it decides where one object ends and another begins. That lego house in the corner – is it one object or hundreds? That sectional sofa – is it one object or several? Is the set of silverware an object or only the knives, forks, and spoons within it? And what of their parts – the tines, handles, and atoms. Are they objects too?

Hume’s mistake, according to Kant, was that he accepted sense data: the idea that the objects we see come before consciousness pre-carved with their boundaries and edges already established. Kant held that the boundaries and edges are where the mind drew them. Kant saw the mind as creating objects by carving up the tapestry of experience (the “manifold”) into discrete segments – by individuating – by deciding where one object ends and another object begins.

Now look at yourself and observe your behavior. How many actions are you performing? The answer, again, depends on how your mind draws boundaries — how it carves and slices actions —how it decides where one action ends and another begins. Suppose you’re going to the store to buy milk. You can say that’s one action, two actions (going to the store and buying milk), or millions (getting the car keys, leaving the house, opening the car door, starting the car, etc.).

Ethics, at bottom, seeks a theory of right action. But, as Kant noticed, there aren’t any actions apart from a principle of action-slicing – apart from how our minds carve up the action stream into discrete action-segments. And different ways of carving up that stream will yield different answers to the question of which action is right, what you should do, or which action would make things go best.

Here’s a quick example. Imagine a gamer staying up late but needing to get up early. Should he play another minute? Probably. After all, he’s having fun and another minute won’t affect his sleep quality. Should he play another hour? Probably not since, tomorrow, he really needs to feel refreshed. What he should do, then, depends on how he slices actions – how his mind carves up the action stream into action segments – on whether he slices it in hours or minutes. If he slices in minutes, then he should keep playing. And if he slices in hours, then he should go to bed.

Kant’s categorical imperative, believe it or not, is his general solution to the gamer’s problem: a way of telling us how to carve up actions so as to comply with reason’s demands. He presents three versions, claiming they’re equivalent even though, on the surface, they look nothing alike. This baffles students and scholars. But if we read Kant as trying to solve problems of individuation — of carving and slicing — then everything falls into place, as I (very briefly) explain below.

The first version tells you to act only on maxims you can will as universal laws. Translation: carve actions coarsely; ignore particular cases and focus on the overarching principle. The second tells you to treat humanity as an end in itself. Translation: carve agents coarsely; imagine that you’re deciding not as a lone, discrete individual but as part of a unified rational collective. The third tells you to legislate as a member of a “kingdom of ends.” Translation: carve actions and agents coarsely.

And why should we carve coarsely? Because rationality loathes contradiction. And contradictions in the will, Kant argued, emerge precisely when we carve our actions too finely. Our gamer, for example, by dividing his evening into endless one-more-minute choices, finds himself locked in a conflict with his own ends. By slicing the action-stream too finely, he creates a trap: each choice appears harmless but their totality defeats his purposes. What looks like a problem of self-control is really one of carving too finely. Indeed, such fine-grained carving may be what all alleged self-control problems have in common.

Parts and Wholes

Shows/theories with strong episodic structures are notorious for having weak finales; if it doesn’t care where you drop in, it doesn’t care where you end up either. The finale is unnecessary; it’s there only because the audience/readership demands it. It’s typically just a montage/summary or a where-are-they-now/declaration-of-future-research-interests.

Larry David, for example, makes great episodes. But he’s uneven with finales, and his best ones – like Curb’s fourth season wherein Mel Brooks’s hidden machinations are revealed – cast that season’s previous episodes in a different light. Seinfeld, however, ended with a montage/summary. Cheers just fizzled out. Hume produced exquisite episodic philosophy – perhaps the greatest ever – but his conclusion to Book I of his Treatise was an extended lamentation on how his skeptical project had turned him into a pariah. “I am first affrighted and confounded with that forelorn solitude in which I am placed in my philosophy,” he opened, “and fancy myself some strange uncouth monster, who not being able to mingle and unite in society, has been expelled all human commerce, and left utterly abandoned and disconsolate.”

And so we come to Blockheads – Arrested Development’s season 4 finale – wherein an Oedipally obsessed show ends in the only way it could: with a son punching his father in the face over a woman who resembles his mother and whom he’s horrified to realize they’re sharing.[1] But, before that happens, we learn George Michael’s secret – the truth about Fakeblock – his privacy software that’s also anti-piracy. It’s a profound revelation — one that re-scrambles so much of what came before. And you want to go back to the beginning and find all the clues you missed.

Perfection in the parts creates imperfection in the whole. The most beautiful face is not just a collection of the most beautiful eyes, mouth, nose, and ears. A happy movie can’t consist of only happy scenes; an uplifting symphony can’t make every note uplifting. Great standalone episodes make for uninspired finales. You like Arrested Development’s first three seasons because you love the episodes. You like the fourth season’s episodes because you love the season.

If you gave up on the fourth season after watching the first episode or the Critique after reading the first chapter, you’ve made a huge mistake. Consider re-watching/re-reading. Consider anustart.

[1] In season 4 episode 4 – the B. Team – Michael recruits Rebel Alley to play the role of his dead wife Tracey, saying “you remind me of the person that it’s based on.” They even look alike.

The whole Dangerous Cousins through-line aside, i never considered how incestuous the show was!

Anyway, i get what the season was going for, but it still pales in comparison to the first three (though i still enjoyed it). The structure was forced upon them because of scheduling i believe, so it really wasn’t as good as it could’ve been. And yes, I’ve watched it twice.

Phenomenal—I loved this!