The Trojan Spork

Cutlery and the Meaning of Western Civilization

The first “fork, knife, and spoon” combo was patented in 1864 by Nathan Ames. But it wasn’t until 1909 that “spork” first appeared in the lexicon. And it wasn’t until the 1970s that sporks upended America’s dynamic cutlery market, still reeling from the twin shocks of disposables and stainless steel. Sporks quickly became “popular” among captive eaters (prisoners, patients, students, soldiers) but made no inroads among the un-incarcerated. Indeed, wherever people had a choice, they flung their sporks into the bay, as the French had done with Coca Cola and the colonists with tea.

It’s odd, though. Americans love novelty, gadgets, the old two-in-one (it dices and it slices!). They love convenience and efficiency, especially if it speeds the trek from plate to mouth. They fold their pizzas, swig milk from cartons, scoop peanut butter with their fingers, spray cheese on crackers, and shoot whipped cream into their mouths straight from the aerosol can.

And yet the spork was scorned, mocked, and banished from polite society – treated with derision and disdain as if it bore an ancient curse. And perhaps, dear reader, it did. For the spork is no mere utensil but a Trojan Horse – a four-tonged nuclear missile pointed at the foundations of Western Civilization – sabotage most innocent and foul. And if the spork should ever return, then you will know the end is nigh.

Western Civilization

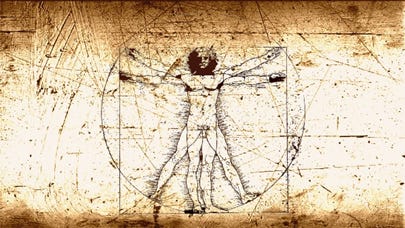

Love it or hate it, the aim should be to understand it. What is Western Civilization? The scientific method, critical thinking, systematic philosophy, engineering, individualism, atomism, materialism, colonialism, democracy, private property, classical music, the assembly line, alcohol, anti-depressants, volumes upon volumes of written law. What does it all mean? What is it all for?

Sophisticates, of course, will tell you that it’s not for anything; to them, Western Civilization, along with everything else, means nothing. Rubes will say it’s for God’s glory, and thus it’s all for just one thing. Pagans and folks looking to deflect the question will say that it’s for many things. But they’d all be wrong. Because Western Civilization isn’t for nothing, one thing, or many things but for converting the one into the many: for converting stuff to things.

Stuff vs. Things

In this world there are two kinds of “things:” stuff and things. Stuff is continuous and undifferentiated: fog, porridge, wetness, dignity. Things are discrete, bounded, and countable: bricks, peas, water molecules, price. Stuff is a lump, a monochromatic canvas, a haze without edges, just one thing. Things are separable, countable, movable, measurable, and divisible. Stuff too can be divided—into things, and those things into smaller things, and those things into smaller things.

To live under a regime of things is to live within a system of lines and distinctions – boundaries and edges – wholes reduced to parts. Under a regime of things, land becomes parcels, wisdom becomes information, honor becomes rights, morality becomes law, dignity becomes status and rank. Wherever a regime of things finds stuff – wholes – it sets about reducing them to parts. It separates one thing from another, studies each in isolation, and then it separates some more.

The scientific method isolates variables. Critical thinking isolates claims. Philosophy isolates concepts, reducing them to other concepts and, ultimately, to conceptual primitives. Individualism is the doctrine of the primacy of parts: the idea that wholes are nothing over and above them. Atomism asserts that reality can be sliced into units so small as to be indivisible. Law creates discrete, separable rules and rights; it’s a system of distinctions backed by threat. The assembly line reduces wisdom to process and the complex to the simple. It’s the apotheosis of part-whole reduction and a ringing declaration that anything wholes can do parts can do better. Parts can do anything better than wholes. No they can’t. Yes they can, yes they can!

Western Civilization is built on the proposition that reality is decomposable and re-combinable: ex uno plura, ex pluribus unum. That’s why capitalism – the method of unlocking value by breaking stuff into things and those things into smaller things – is its economic engine; why materialism – the worship of things – is its ostensible religion; and why democracy – the reduction of society to individuals followed by their recombination into a single unit – is its conception of the end of history.

Forks, Spoons, and Knives…Oh My!

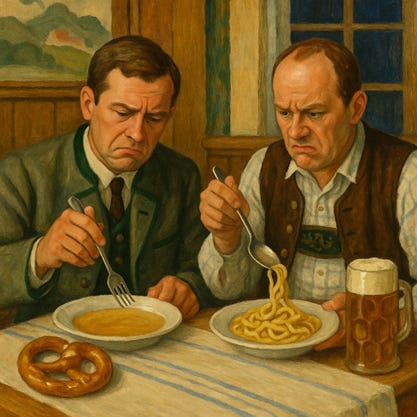

Spoons are for eating stuff. Forks are for eating things. And there’s no Western Civilization without the stuff/thing distinction.

Forks handle discrete, bounded items: chunks of meat, individual vegetables, pasta strands that can be speared. Spoons handle continuous, flowing matter — soups, stews, porridges, puddings, sauces — the kind that takes the shape of its container but, in itself, has no shape at all.

Knives – the foundation of Western metaphysics – fill out the triad by slicing, separating, converting stuff into things and big things into smaller things. They’re the carvers — the creators of distinctions. Wherever they cut, they make a line, separating one thing from another, creating two things out of one.

Knives, then, are for separating. Forks are for eating what’s been separated. And spoons are for eating what cannot be separated.

And so it’s no wonder that the Western mind would see a utensil that combined the functions of a fork and spoon as an abomination – a violation of its deepest and most sacred covenant. When Western man beholds his dinner plate he demands to see food. But, even more, he demands to see order — clarity, determinacy, distinctions — clear separation between what can be separated and what cannot be. Western Civilization can endure all manner of calamity but not the chaos of a thrice daily reminder that there isn’t a distinction between stuff and things.

“God does not play dice with the universe,” said Einstein. “Nor with dinner,” those patriots must have thought as they hurled their sporks into the bay. Meals aren’t just meals; they’re rituals — reenactments in miniature of larger existential dramas. To accept the spork would have been to deny the drama at the heart of all our dramas — the ever-present, underlying, percolating tension between wholes and parts, stuff and things. It would have been to eat without distinction — to blur the line between what can and can’t be separated — to challenge the viability of drawing distinctions at all.

The Undivided Bowl

Grant that Western Civilization is for converting stuff to things. But to what end? What’s it all for?

Perhaps it’s all for going back to the beginning – for coming home. Call it a return to innocence, undoing the fall of man, or rediscovering the primordial soup – the stuff from which all life sprung. Whatever you call it, there is an arc of history, and it bends towards wholeness; if you keep reducing wholes to parts, you eventually return to wholes.

Suppose the universe were a giant, undifferentiated cucumber. By slicing it in two, you’d create two things out of one. But if you kept on slicing, you’d reduce those things to finer things and, eventually, to stuff: puree. Break stuff into enough things and things will eventually become stuff again. First the analog (stuff) becomes digital (things) and then, when it’s sufficiently fine-grained, it returns to analog.

But, as any hipster will tell you, when the digital returns to analog it does not return unchanged. And so it is for returning to stuff in general. You can’t replace a broken vase by gluing it back together. Animation — even at 24 frames per second — isn’t quite reality. The cucumber’s return to stuff — puree — isn’t exactly a return to the beginning. A dancer can take a single continuous movement and “break” it into so many pieces that it looks continuous again. But the smoothness of a thousand pieces in unison is not the smoothness of an undivided whole.

Western literature’s main archetype is the hero’s journey. The hero leaves home and plunges into darkness – chaos – disorder. He subdues the chaos with his trusted blade, cuts it into pieces, gives it shape, imposes upon it a system of distinctions. Eventually he returns home, victorious and spent. He comes full circle.

Only it’s not a circle but a spiral. The “home” to which he returns is both his home and not his home — same but different — familiar and strange. There’s a difference between stuff and stuff divided into things and then reconstituted. You can’t eat from the same bowl twice.

Fascinating stuff (or thing?)!!

This is marvellous Misha