What if there aren't any problems?

On the perils (and necessity) of deriving an "ought not" from an "is"

These days philosophy looks a lot like asset management. Once upon a time philosophy was poetry, imagination, the unfolding of absolute spirit, or just an excuse to drink wine. But not anymore; not in this economy. Now you invest in projects, hedge your positions, cash out ideas, build intellectual capital, diversify your portfolio, and hope your theories pay out.

The dollar may the global market’s reserve currency but problems are the currency in the marketplace of ideas. Theories are judged by the ratio of problems gained to problems solved. Is your theory crazy? That’s a problem. But it may not be a big problem if your theory solves other problems. Solve more problems than anyone else and philosophers will take you seriously, no matter how crazy your ideas. Just ask the great and redoubtable David Lewis.

The Scorekeeper

David Lewis was a clever man—a very clever man—and as serious as he was clever. He was much too serious for small talk. But he had a fascination with trains, and would happily discuss them, but only with people who knew as much about them as he did. This was funny because everyone wanted to talk to David Lewis. For decades he was Princeton’s leading light and arguably the consensus choice for all-around analytic brainiac-in-chief. And if you wanted his attention you had two choices: philosophy or trains. Many sensibly (but unwisely) chose the latter, and sealed their fate. Misha nearly fell into the trap himself, and was spared abject humiliation only by a kind stranger who pulled him aside and warned him not to talk to David Lewis about trains unless he could tell a cowcatcher from a wing plow.

Lewis is known for defending modal realism: the view that possible worlds exist, literally and concretely. There’s the way things are and the way things could have been, and there’s a world for every way things could have been. There’s a world where Britney Spears reinstated the Roman Empire, Hillary Clinton married Donald Trump, Gandhi invented Facebook. There’s a world where we didn’t write this sentence. There’s a world where we wrote it twice. “Show me a possibility,” Lewis might well have huffed, “and I’ll show you a world that instantiates it.” And these worlds aren’t just thought experiments or abstractions, he insisted. They’re real. They’re out there. And they’re spectacular.

But just how real are they? Could you visit them, spend a night in their cloud castles, sip tea with your significant other, who, in this case, happens to be you? Could the Gandhi who led Indian independence break bread with the Gandhi who invented Facebook? That’s where Lewis drew the line. Possible worlds are real, he said, but there is no overlap between them. There’s no trans-world fraternizing or mingling. And that other “Gandhi” isn’t Gandhi but his counterpart: he may look like Gandhi and act like Gandhi but the two are distinct.

Needless to say, modal realism has problems. It’s crazy. The ban on trans-world fraternizing seems arbitrary. The line between counterparts and impostors is anything but clear. But Lewis defended modal realism with great gusto, and philosophers take it seriously, because it solves a lot of problems. It demystifies modal statements (i.e. statements of possibility and necessity). “I coulda had class,” laments a broken Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront. “I coulda been a contendah.” Sure, buddy. But what does that even mean? What fact about the world makes it true that you could have been anything but the palooka that you are? According to Lewis, it means, and is made true by the fact that, there exists a possible world in which Brando’s character (or his counterpart) was a contendah. Briefly, X is possible if there exists a world where X is true, impossible if there is no such world, and necessary if X is true in all possible worlds. Modality—philosophy’s feral child—had been domesticated.

If you’re not a metaphysics groupie Lewis’s solution might leave you cold. Personally we think he chased a bird out of the living room and into the kitchen, demystifying modal statements but mystifying possible worlds, shifting the problem from semantics to metaphysics. But metaphysicians swooned. And Lewis made a strong case that his problems weren’t worse than anyone else’s. Sure, he’d admit, modal realism seems crazy. And so he had a bullet to bite. “But show me another theory of modality,” he might well have chortled, “and I’ll show you a mouth full of bullets!” And he had a point. Lewis may have sacrificed common sense but his rivals sacrificed modal grounding, objectivity, or the right to talk about possibility at all. “Besides,” he might have added, “look up at the scoreboard!” In the end we’re judged on our ratio of merits to demerits—problems solved to bullets bitten—and Lewis had the biggest, baddest ratio in town.

The Great Philosophical Bear Chase

Few philosophers accept Lewis’s modal realism. But they almost all accept his method. It’s as if a giant scoreboard hovers over them—a great celestial balance sheet—on which every philosophical idea is represented. An idea’s rank depends on its PS:BB ratio (problems solved to bullets bitten). And the aim, of course, is to climb higher, either by solving problems, spitting out bullets, or jamming them into other people’s mouths. Alas, the scoreboard is itself an idea, and so must also be represented (on itself), creating a paradox that, as of this writing, only the blockchain has been able to resolve. But that’s a story for another time. For now, just picture a giant ticker in the philosophical thought exchange, constantly updating, anxiously observed by the people below.

It wasn’t always so. Once upon a time, a problem was a problem. The truth didn’t have problems. So if your theory had problems, it wasn’t true. There were no scoreboards, balance sheets, or ratios. Socrates treated problems as refutations rather than demerits. He had a knack for finding problems, found them everywhere, and concluded that he knew nothing. Lewis also had a knack for finding problems, found them everywhere (including in his own views), and concluded that he knew enough.

Once upon a time, a problem was a problem. The truth didn’t have problems. So if your theory had problems, it wasn’t true.

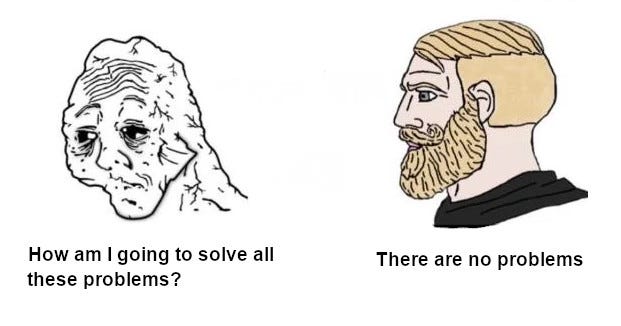

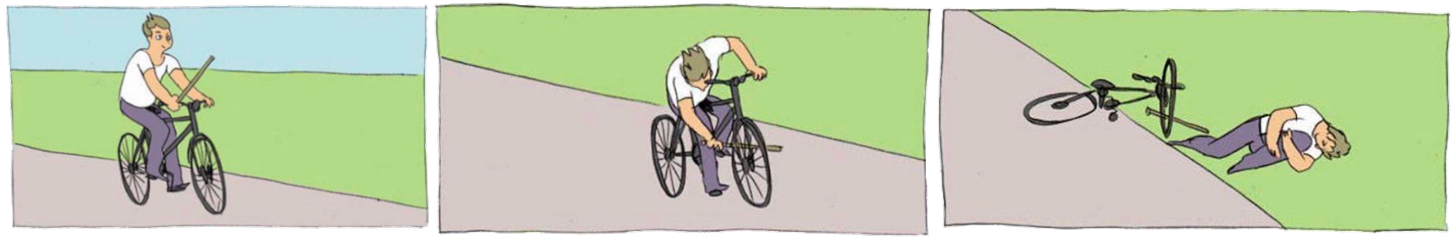

Somewhere between Socrates and Lewis philosophers stopped trying to solve problems and started trying to manage them. It’s like the joke about two hikers who encounter a bear. The first starts lacing up his sneakers. “You can’t outrun a bear,” his friend says in disbelief. “I don’t have to outrun a bear,” the first replies. “I just have to outrun you!” Seemingly unable to outrun their problems, philosophers have decided to outrun each other.

Philosophers, of course, don’t describe their methodology as a great and frantic bear chase but as reflective equilibrium. We can’t preserve all our intuitions, the thought goes, but we can’t just jettison them either. And so we strike a balance, adjusting our positions one way and then another so as to minimize intuitive distress. Every intuition preserved counts in your favor. Every intuition rejected counts against you. Make no mistake: someone is going to get mauled. Neglect your PS:BB ratio and it could well be you.

Problem Nihilism

But have we been too quick to throw our colleagues to the bears?

The bears sniff out discarded intuitions. But what if we didn’t discard any intuitions? The bears attack the most encumbered runners. But what if there were no encumbrances? What if there were no bears?

Here’s a theory whose PS:BB ratio blows every other theory’s out of the water. It solves more problems than modal realism—more than any other theory on the scoreboard—and all without turning any intuitions into bear food:

Problem Nihilism: There are no problems.

In other words, there is no work to be done, no changes to be made. There is no distinction between how things are and how they ought to be. Common sense needs no modification. Our intuitions are all correct. Sometimes they conflict, but that is not a problem. Because there are no problems. There are no moral problems, no intuitive problems, no philosophical problems, no logical problems. Problem nihilism doesn’t solve just any problem. It solves them all.

As long as problem nihilism draws breath it’s hard to justify doing philosophy. We should know that there are problems before trying to solve them. And if, like Lewis, you judge philosophical theories by their scoreboard rank—their ability to outrun other theories—you may as well stop now: problem nihilism outruns them all.

If you want to be a problem realist—if you want to say that there are problems—you have a hard case to make. Problem realism, after all, is riddled with problems; it can tolerate anything but their absence. Even worse, any objection to problem nihilism will beg the question against it. Denounce it as unintuitive, inconsistent, or absurd—hurl at it whichever epithets you like—and they’ll just bounce right off. For how do you establish that being unintuitive, inconsistent, or absurd are problems?

The problem nihilist’s strategy is comically simple but impenetrable. It’s a favorite of obstinate children and the bane of mothers everywhere. Consider:

Mom: Clean your room!

Kid: Why?

Mom: Because it’s dirty.

Kid: So?

Mom: A dirty room attracts pests.

Kid: So?

Every “so” accepts the facts and demands a further explanation for why they constitute a problem. And every explanation falls short. The mother knows it’s hopeless. Reason has been defanged and outwitted. And so she opts for other means.

An argument with a problem nihilist would be only slightly more sophisticated:

You: What about the problem of free will? It seems like our actions are causally determined and thus not free. But it also seems like our actions are free.

PN: Yes, it all seems that way. But that’s not a problem.

You: It is a problem because those intuitions contradict.

PN: Yes, they contradict. But that’s not a problem.

You: But it’s logically impossible for a contradiction to be true.

PN: Yes, but that’s not a problem.

You: But if contradictions are false, then we must be wrong either about predetermination or free will.

PN: Yes, that follows. But that’s not a problem. Just because we’re wrong doesn’t mean we should change our theory.

You: But that’s what “wrong” means!

PN: Yes, by definition, if we’re wrong then we should change. But that’s not a problem.

You: Now you’re contradicting yourself!

PN: Yes, I’m contradicting myself. But that’s not a problem…

It’s impossible to debate someone who’s indifferent to any tension between how things are and how they should be. When we try to refute the problem nihilist, we present them with considerations that strike us as problems. But the problem nihilist will just validate our considerations but refuse to grant them the status of problems. And if you try to prove them wrong, you’re doomed. It always takes an extra step, an extra assumption, to show that something ought to be different from how it is. You can’t derive an ought not from an is. And so the problem nihilist cannot be refuted.

We lack a rational basis for believing that there are problems. We cannot prove, but only assume, that problems exist.

Now what?

So should we abandon problem realism, pack up our scoreboards, tear up our balance sheets, discard our ratios? Should we become problem nihilists? Please. You flatter yourself. You’re not cool enough to be a problem nihilist. Besides, there’s no quitting problem realism short of quitting life itself.

As metaphysicians puzzle over possibility so philosophers of mind puzzle over agency. What distinguishes events from actions—happenings from doings—they ask? What’s the difference between jumping off a cliff and falling off one? Doings, of course, have an intentional, purposive quality. But what does that mean? These are ancient questions and there are plenty of dull theories from which to choose. But consider a bold conjecture: to be an agent just is to irrationally derive an “ought not” from an “is.” It’s to see yourself as having problems. The cliff jumper sees himself as on a ledge and thinks he should be in the air. The cliff faller sees the ledge and sees the air and goes about his business.

Every action begins with an intention—a visualization of a different future, a new way the world could be—and the conviction to achieve it. A problem is just a gap between the world and that visualization. And an action is just an attempt to close that gap. Without problems, there’d be no actions; only spasms, happenings, events. To act intentionally, then, just is to be a problem realist. Our irrational commitment to the existence of problems is why we’re alive. Problem realism is agency. Problem nihilism is death.

The good news is that problem nihilism leaves philosophy exactly where it was: in perpetual stalemate. You can’t refute the problem nihilist but he can’t refute you either. What could he say? That your view has problems?

But even if philosophy can escape the nihilist’s grip, the same cannot be said about its favorite method. Imagine discovering a spell that gets you all the money you want, for free, forever. And now imagine Wall Street the next day: no suits, no brokers, no long coffee lines. If making money was that easy, the financial sector would collapse. Now imagine discovering a spell that solves all problems, for free, forever; and now imagine philosophy the next day: no balance sheets, no scoreboards, no ratios. Problem nihilism is too obvious, too cheap and too effective to ignore. No theory will solve more problems. No theory will preserve more intuitions. Its PS:BB ratio is bear-proof. It cannot be outrun.

It’s game over for reflective equilibrium. Problem realists will just have to find another way.

But how? Lewis, after all, was a very clever man. Cost-benefit analysis, he reasoned, optimizes for problems solved. So if philosophy’s aim is to solve problems, it follows that it can do no better than cost-benefit analysis. Right?

Beware of arguments that seem so trivial yet so informative. For Lewis was mistaken. Philosophy’s aim may be to solve problems. But that doesn’t mean that that’s its purpose. And purpose trumps aim.

Imagine an archer who brings a date to a range. He aims at a target. But his purpose is to impress. Would Lewis, then, recommend that he maintain complete silence, spend hours inspecting his bow, assume an absurd posture, make his date turn around so that she doesn’t distract? No. Because the aim is not the purpose.

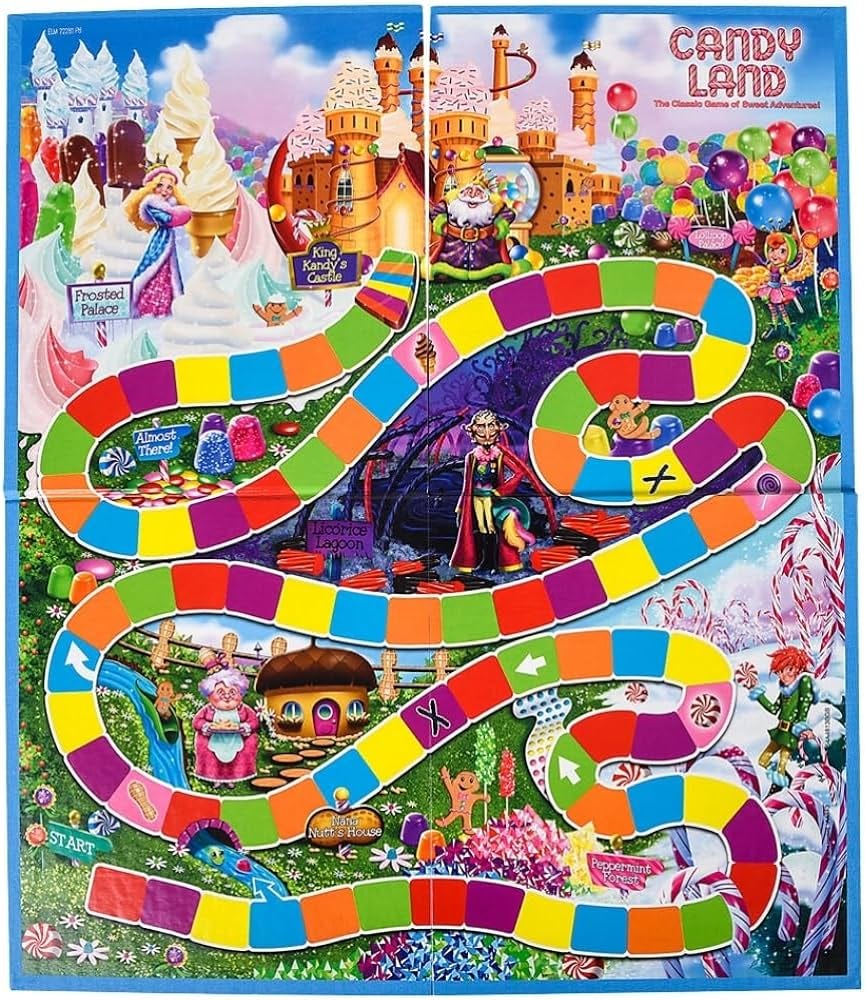

Or take a game like Candyland, which you win by landing on the final square. It doesn’t take a scheming tot very long to figure out that this goal is trivially easy to achieve: just move your piece to that square. But that is not allowed because a game’s goal is not its purpose. The goal is to land on the final square but the purpose is to have fun. And rules, like problems, are arbitrary stipulations that advance the purpose by making the goal harder to achieve.

If Candyland’s purpose was to see your piece on the final square, you’d just put it there and stop playing. And if philosophy’s purpose was to solve problems, we’d all be problem nihilists and stop philosophizing. Yet here we are, philosophizing. So Lewis was wrong.

But then why do we do philosophy? Why solve problems the hard way? Why intensify the agony? Well, why not just walk up to the bulls-eye and stick an arrow in it? Why not just move your piece to the final square? Why write a symphony when you can just write the climax? Why make a series when you can just shoot the finale? Why prolong life when dying is easy? Why do anything at all?

These questions are just so many masks for the same core mystery: why be a problem realist when you can be a problem nihilist? Why struggle against problems that can be so easily solved? We can’t tell you the meaning of philosophy any more than we can tell you the meaning of life. But we can tell you that they’re the same.

Problem nihilism targets life itself. Philosophy is just collateral damage, because philosophy is but a microcosm of life, the paradoxical pursuit of an ultimate solution we do everything we can to avoid. The destination is an excuse for the journey—the means justify the ends—and to optimize is to miss the point. St. Augustine prayed, “Lord, make me chaste - but not yet!” And so goes the prayer of every philosopher, of every living thing: “Lord, solve my problems - but not yet!”

The end is nigh for actuarial philosophy. Its scoreboard is broken, its currency debased. Optimization is out; inefficiency is in. And what poetic beast, its hour come round at last, slouches towards Princeton to be born?

I believe that entropy is the fundamental Law of everything, This "everything" can exist only if a resistance forces are active and more powerful than the forces of degradation. Those forces weakened due to many different processes. The result is well formulated at the end of your article: "The end is nigh for actuarial philosophy. Its scoreboard is broken, its currency debased. Optimization is out; inefficiency is in."

Surely, by it's own lights, problem nihilism solves zero many problems. In order to solve them, they must have been problems— a precondition denied by the nihilist. So the solution:bullets ratio for nihilism is 0:n. That's bad even if I like the taste of nihilism so much that I find all the so-called bullets to be candy.