Chances are that there’s already some shit in whatever you’re eating. But you probably think that I couldn’t make you eat more of it, at least not without resorting to unsavory means. But you’d be wrong, and Derek Parfit’s trailblazing work in population ethics explains why. Parfit could make anyone eat shit – willingly, gladly, and in quantities you could scarcely imagine – and not just in the seminar room. Bribery and blandishments did not become him. He couldn’t hurt a fly. He couldn’t tell a lie. But he could make you eat shit. All he needed was your rationality and the power to make things better.

Like a cross between Monty Hall and Don Corleone, Parfit’s gambit was to make you an offer that you couldn’t rationally refuse. Or many such offers, really, in rapid succession. Suppose that you’re sitting on a park bench about to eat a sad little veggie burger – the A-burger – that happens to contain, say, 50 molecules of shit. That’s when Parfit swoops in, like Tarzan on a vine, and offers to replace your sad little burger with another – the B-burger – that’s just like the A-burger except that it’s twice as delectable and contains just a bit more shit. A burger with fifty molecules of shit is barely distinguishable from one with a hundred; even the world’s leading scatologists can’t tell the difference. But the B-burger is twice as delectable. You’d be crazy – irrational – to refuse. And Parfit knows it.

But no sooner do you accept the B-burger that Parfit offers you another – the C-burger – that’s just like the B-burger except that it’s twice as delectable and contains just a bit more shit. If you’d be crazy to refuse B for A, you’d be crazy to refuse C for B. And D for C, E for D, and so on, until you reach the Z-burger – the last in Parfit’s stash – twice as delectable as Y but not so as compared to A because it’s so profoundly full of shit. Welcome to Derek Parfit’s repugnant conclusion. Enjoy your meal!

Ironically, Parfit named the repugnant conclusion after a thought experiment whose conclusion wasn’t especially repugnant and bore no relation to shit:

“For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living.”1

Written on the subway walls, you could be forgiven for overlooking that thought experiment’s profundity. Parfit overlooked it too, and he spent decades digesting, and stewing in, its implications. Imagine a world – the A-world – of 10 billion happy people. Now imagine another – the Z-world – of 100 trillion people, each of whom have lives that are just barely worth living. The A-world seems better than the Z -world; if God had to choose which to create, he should create A. And yet Z may exceed A in total happiness. But the real clincher is that you could transform A into Z in such a way that each step would register as an improvement over what came before. You just keep doubling the population and ever-so-slightly reducing each person’s happiness. You move from A to B to C and all the way to Z. It’s like the burger: you keep doubling the delectability and adding just a bit more shit.

Forget about worlds; the paradox is clearest in the case of individuals. Suppose you crave a beach vacation. Your travel agent pitches you a three-day stay at the most beautiful resort you’ve ever seen: the most pristine beaches, dolphins that swim right up to you, the water a perfectly translucent aquamarine. But before you accept she pitches you another: a six-day stay at a stupendously beautiful resort that’s just slightly, almost imperceptibly, less impressive: the beach is just a palm tree short of perfection, the dolphins swim right up to you but not on Tuesdays, the water is just a hair less clear. Since an experience’s value depends on both intensity and duration – on how good it is and how long it lasts – it makes sense to sacrifice a droplet of the one for a deluge of the other. And so, the second vacation is better than the first. And the third (a twelve-day stay at a beautiful resort that’s just two palm trees short of perfection, etc.) is better than the second. And the fourth is better than the third, and so on. But the first is better than the last: a veritable eternity at a windy beach full of sand crabs, dolphins that mock your laughter, palm trees that sway to the tune of your least favorite song.

You might be wondering how, beyond the seminar room, any of this could matter. After all, you don’t have unlimited vacation time, you can’t create worlds, and, after several rounds of Parfit’s burger game, you could probably just take, say, the G-burger and call it quits. If that’s what you’re thinking, then I admire your pragmatism. I truly do. But the repugnant conclusion, I’m afraid, does not. It cannot be confined to a seminar room. It cannot be imprisoned in an ivory tower. It is a force more powerful than gravity and almost as ubiquitous. Whether or not you know it, you are in its grip. It’s chipping away at you, sapping your energy, dragging you down. It dragged down Parfit too, who had correctly identified the force by which he’d be dragged down but mistook it for a curiosity about goodness, like Darwin if he’d mistaken natural selection for a curiosity about finches or Newton if he’d mistaken gravity for a curiosity about apples.

Imagine an enemy who could enfeeble you by making you stronger, shrink you by making you bigger, take you farther away from your destination by bringing you closer with each step.

Alas, the repugnant conclusion will drag down us all. And so you might as well get to know it, partly to delay it, partly to befriend it, but mostly to appreciate its craft. Because there isn’t a more powerful superhero or a smoother criminal. Superman, they say, could outrun speeding bullets and leap tall buildings in a single bound. But the repugnant conclusion’s powers are real, weirder, and vastly more impressive. It’s to turn a thing into its opposite: virtue into vice, love into hate, life into death, reason into ruin, A to B to C and all the way to Z. Imagine an enemy who could enfeeble you by making you stronger, shrink you by making you bigger, take you farther away from your destination by bringing you closer with each step. The repugnant conclusion is a foe like none other. More than heart disease, it is humanity’s silent killer. More than AI, it is humanity’s greatest threat. Pragmatism will not save you and may even hasten your demise. Ignore it if you wish, but you can’t just decide to not eat shit.

Loved and Feared

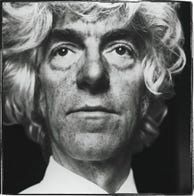

Derek Parfit was a man possessed. He was a smart person’s idea of a super smart person: eccentric, disorganized, disheveled, frightfully articulate, a patrician’s air and a mop of white hair. He wrote feverishly, circulated his manuscripts widely, revised them endlessly, answered every question, chased down every lead. Had the world been less obsessed with metrics and credentials he’d probably have been content to think and write and talk and never to have published. To publish is to chain oneself to a position – to articulate one’s limits – to freeze one’s thoughts in time. In a way it’s an admission of defeat: a declaration that one’s thoughts have bottomed out and that one can think no more. And that’s just what Parfit wanted save the declaration of defeat. He wanted his thoughts to touch bottom. He wanted his to be the final word. And yet their flow could not be stilled.

I met Parfit on several occasions but I got to know him mainly through Larry Temkin – my thesis advisor and Parfit’s former student – who’d regale us with tales of Parfit’s eccentricities and brilliance. Under Parfit’s tutelage, Temkin wrote a dissertation on the nature of inequality. As Temkin tells it, Parfit had him write 50 pages on the topic, which Parfit returned without comment and a request for 50 more. This continued until Temkin had written about 300 pages, at which point Parfit systematically tore it all to shreds. It was the philosophical equivalent of a massacre. A year’s labor lay in ruins. He then told Temkin to begin anew, as he was now prepared to write in earnest.

In 2002 I attended a Festschrift in honor of his 60th birthday. Many of the world’s top ethicists were there. Most of them had worked with Parfit or had been trained by him. In one way or another, they were all his students. I was there for the philosophy but mostly for the spectacle. Parfit was being honored in the only way philosophers know how: by being publicly eviscerated. Speaker after speaker would rise, approach the podium, and launch into a withering critique, trying to do to Parfit what he had done to Temkin two decades prior. Parfit would sit in stony silence and then leap to his feet the second they were finished, well into rebuttal before even reaching the podium, as if he were a gladiator determined to show that none of his opponent’s blows had landed and that not a drop of his blood had been spilled. Occasionally the proceedings would veer into eulogy – it was, after all, a celebration of a lifetime’s worth of achievement – but Parfit would have none of it. “I’m not dead yet,” he’d remind the room. In all it was a riveting performance full of pageantry and drama and what I’m sure was some top shelf philosophy, though nothing comes to mind in particular. In the end the weary scholars shuffled out of the arena but Parfit was as spry as ever. It seemed the only way to beat him was to outlast him or to render him speechless. By that standard, there was no doubt who had won.

Arguments can always be made clearer; they just can’t always be made clearer without adding just a bit more shit.

Parfit was a towering figure, unusually approachable for one with such a lofty perch and reputation, willing to read and comment on just about anything. He spoke kindly but in a way that conveyed that he had already thought of everything. He was gentle and terrifying, loved and feared. But though he lived among the folk and called some of them his friends his true home was in the clouds – the realm of ideas – where he was an unabashed perfectionist, committed to precision in argument above all else. He served the god of clarity if he served any god at all. But serving such a god is fraught with peril, for though the god of clarity is neither vengeful nor capricious he is perpetually displeased. Arguments, after all, can always be made clearer. There is always another a phrase to disambiguate, a distinction to draw, a hair to split. And Parfit, ironically, had discovered the true source of that god’s pique. But, like Columbus mistaking Cuba for the East Indies, he couldn’t quite lift himself above his biases to see what stared at him so plainly. Arguments can always be made clearer; they just can’t always be made clearer without adding just a bit more shit.

Much Ado about Goodness

Philosophers come in many flavors: ethicists, logicians, epistemologists, philosophers of mind, etc. But there aren’t any philosophers of coconuts. Why? It’s not because coconuts aren’t interesting but because they’re not special. Their philosophical problems are generic, shared by pineapples, plums, kumquats, and the like. A philosophy of coconuts would make about as much sense as a philosophy of chairs. Back in 1903, a promising young lion – G.E. Moore – took Cambridge by storm by declaring that ethics was special. Goodness, he assured his brethren, was not like coconuts.

Goodness was special, thought Moore, because it couldn’t be defined in terms of any “natural” property like pleasure, desire fulfillment, or anything that could be scientifically measured, studied, or observed. And a simple argument – the open-question argument – showed why. Pick any natural property with which goodness might be identified (I’ll pick pleasure for the sake of illustration). Now consider the question: X is pleasurable, but is X good? Whatever the answer, the question seems sensible. It’s an open question. And that reveals that “goodness” and “pleasure” are not synonymous. After all, if they were synonymous, then asking “X is pleasurable, but is X good?” would be like asking “X is pleasurable, but is X pleasurable?” or “X is good, but is X good?” But those are not sensible questions. They are closed. So “goodness” can’t just mean “pleasure.”

In its day the open-question argument held sway but, over time, its power waned. Philosophy of language was then ascending, and the complexities it introduced around the notion of meaning undercut the authority of Moore’s stark claims. It turned out to be an open question whether a question was an open question. Quine’s “Two Dogmas of Empiricism” (1951) deployed a version of the open-question argument against the concept of a bachelor, which philosophers had hitherto assumed could be fully defined as an unmarried male. In the 1970s Hilary Putnam further muddied the waters by arguing for content externalism: that meanings aren’t entirely in the head. But nothing crushed its spirits quite like Naming and Necessity (1980), in which Saul Kripke argued that some scientific claims, like “water is H20,” are necessary truths. Right or wrong, Kripke’s work implied that “Is water H20?” might be a closed question. But it’s nothing like “Is water water?” or “Is H20 H20?”

By the early 1980s the open question argument was in tatters, and with it the idea that goodness was special. Maybe ethics wasn’t all that different from the philosophy of coconuts after all.

But if there were any doubts, Parfit’s magisterial Reasons and Persons (1984) silenced them. In the introduction he set himself the task of demonstrating that progress in moral philosophy was possible. He concluded by admitting he had failed, but in a way that made him hopeful that others might succeed. And yet he had succeeded, not by making moral progress but by validating moral philosophy’s pretensions as a stand-alone subject. Like Moore, he had given ethicists a reason to believe their field was special. Goodness, he showed, was privy to all manner of paradox, none more dastardly than the repugnant conclusion itself. A seemingly unique and confounding mystery lay at the heart of ethical dispute. Parfit had breathed new life into ethics by showing that there might not be any such subject – that ethics might be incoherent. It was the best news that ethics had had in years.

The Man Who Mistook the Future for a Paradox

But things were not as they appeared, for Parfit had discovered not a paradox of goodness but something larger and vastly more disturbing: a crack in the foundations of analysis, a tripwire in reason, a doomsday device within thought itself. In essence, he had discovered a bomb. And the bomb was ticking.

Suppose I told you that the world’s biggest lake can’t support rocks or plants, that you can’t drown in its waters, and that you can enter and exit it but you can’t get wet. How? Take a medium-sized lake – the A-lake – and slightly decrease its depth and width but extend its length such that, on the whole, its volume increases. That’s the B-lake, and it’s bigger than the A-lake. Repeat this process and you’ll create the C-lake, which is bigger than the B-lake. Keep going and you’ll eventually create the lake I’m describing – the Z-lake – absurdly long but with hardly any depth or width at all – a veritable string of water molecules extending into the outer reaches of space. B is a bigger lake than A, C is a bigger lake than B, and so on. But A is a bigger lake than Z.

Suppose I told you that the mightiest castle walls couldn’t stop a child – that she could punch a hole right through them. How? Imagine being lord of a castle whose walls are thick but not especially tall. I increase their height a few inches but at a very slight, barely perceptible reduction to their width. Those are the B-walls, and they’re mightier than the A-walls. Repeat this process and you’ll produce the C-walls, which are mightier than the B-walls. At some point you’ll worry about the disappearing width, but a tiny enough reduction in width can always be offset by a large enough increase in height. Eventually I saddle you with the Z-walls: absurdly tall but thin enough that even a child could muscle through them. B is mightier than A, C is mightier than B, and so on. But A is mightier than Z.

Now imagine being an early astronomer working on the geocentric model. Occasionally you encounter observational discrepancies: contrary to your model, a planet temporarily reverses course. You add an epicycle – a loop within the planet’s orbit – and the discrepancy vanishes. That’s the B-model, and it’s more accurate and useful than the A-model. But then you find another discrepancy, and another. And so you add more epicycles, moving from A to B to C and all the way to Z. By the end you’re adding epicycles to epicycles, loops within loops, each time making the model just a bit more useful and adding just a bit more shit. But in the end the model is hopelessly cluttered and unwieldy. You try cramming in another epicycle and, like a house of cards, it all implodes. The bomb goes off. B was more useful than A, C was more useful than B, and so on. But A was more useful than Z.

Now suppose you’re sitting on a park bench about to do some serious philosophy. You’ve got a thousand distinctions in your quiver, each extremely useful, armed and ready to deploy. That’s when I swoop in, like Parfit on a vine, and offer to double your distinctions to two thousand, each just slightly, almost imperceptibly less useful than the ones you have now. You hate to compromise, but doubling your distinctions more than compensates for the loss. But no sooner do you accept that I offer you another – the C-quiver – which is just like the B-quiver except that it has twice as many distinctions, each just slightly less useful. If you’d be crazy to refuse B for A, you’d be crazy to refuse C for B. And D for C, E for D, and so on, until you reach the Z-quiver: a hundred trillion distinctions, each of which is hardly worth making.

Humanity suffers from the crippling problem that it’s always possible to make things x-er (bigger, better, stronger, clearer).

Parfit’s mistake was the same as Moore’s. Moore thought that the open-question argument showed that goodness was special. But that argument can be deployed against any conceptual analysis (e.g. coconutness, chairness, bachelorhood); it doesn’t single out goodness in particular. Parfit thought that the repugnant conclusion showed that goodness was special. But the repugnant conclusion can be deployed against any natural relation – is-bigger-than, is-mightier-than, is-clearer-than, is-more-useful-than – and not to goodness (or is-better-than) in particular. The open-question argument and the repugnant conclusion are manifestations of the same general problem – a failure of analysis – a gap that forms whenever one seeks clarity by breaking wholes into parts. They’re no more endemic to goodness than natural selection is to finches or gravity is to apples.

Humanity suffers from the crippling problem that it’s always possible to make things x-er (bigger, better, stronger, clearer). That, plus the desire, is all the repugnant conclusion needs to turn goodness into badness, strength into weakness, reason into madness, clarity into mud, A to B to C and all the way to Z. It targets governments, bureaucracies and institutions but it targets people too. We’re all trying to make ourselves x-er along some dimension or other, moving along a continuum, making incremental improvements and each time adding just a little bit of shit. And shit accumulates. Marx thought that capitalism would collapse under the weight of its own shit (its own “contradictions,” as he lovingly put it). The repugnant conclusion shouts back: so shall you all!

Derek Parfit is rightly remembered as a great philosopher. But in time he may come to be remembered as a prophet. And his most important prophecy – the repugnant conclusion – was mistaken for ethical insight because it validated ethicists’ sense that theirs was a truly noble quest. But it was profoundly insightful; it just didn’t reveal anything about goodness in particular. Parfit had seen the future. He had discovered one of nature’s most potent forces – the form of change – how a thing becomes its opposite – but saw only a puzzle about the good. And he would try to solve that puzzle in the only way he knew how – through analysis – by breaking wholes into parts – seeking clarity by way of distinction. But the future he had seen was his own. He would go on multiplying distinctions beyond necessity, adding epicycles to epicycles, loops within loops, making things just a little clearer and adding just a bit more shit. Each time the god of clarity would rejoice. But, in the end, even he can’t bear the sight of his creation. He emerges from his cloud castle, gazes over fields of endless fences, barricades, and demarcations, wires upon wires, loops within loops, and wonders if he’d have been better off never having drawn any distinctions at all.

Quoted from Reasons and Persons, ch. 17.

Consider peer review as a repugnant conclusion. A paper gets a bunch of comments from reviewers. Responding to each particular comment could make the paper better. But if you respond to every comment you’ll likely make the paper worse.

"Written on the subway walls, you could be forgiven for overlooking that thought experiment’s profundity." I am not written on the subway walls, thankfully. (This sentence begins with a misplaced modifier.)